Name of author: Azhan Saleem (Student, National Law University, Delhi)

Introduction

The developments in the modern technological world have given rise to new dimensions in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Such unprecedented developments require deliberation and modification of India’s existing Intellectual property (IP) law framework. The main aim of this article is to address the implications of the work generated by Artificial intelligence, specifically in the realm of copyright law, and to find a probable solution by navigating the possibilities of recognizing the legal personhood of AI. Traditionally, It has been a settled principle that only humans are capable of producing such novel and creative works capable of legal protection under IP law. However, the advent of Artificial Intelligence has led to an evident shift from the traditional human-centric approach to consideration of prospects of AI for copyright protection. Establishing the IP rights of work generated by entities working autonomously without human input is an insurmountable challenge, at the same time, there is little judicial or legislative backing for such works.

In light of this, it is imperative for us to navigate the possibilities to grant legal personhood to AI to protect its intellectual property and prevent misuse. Therefore, For the purpose of our inquiry, it is essential to do a comparative analysis of the nature of work generated by human beings and AI entities. The next section will deal with this aspect further.

Nature of Work

If human beings possess certain qualities on the basis of which certain rights and obligations are granted to them, the moot question arises from this proposition is whether such qualities are restricted to humans or some other entities (especially AI) are capable of generating works akin with human creativity. As AI continues to advance, impacting various fields, the question of AI-generated works has become even more important. Artificial Intelligence can be categorized into weak AI, also sometimes called narrow AI, which is capable of doing a particular task that it is designed to do. It cannot go beyond the input which was provided by the developers at the initial stage. Programs such as ChatGPT or Gemini are based on this weak AI model. On the other hand, strong AI is capable of learning, thinking, or adapting from the initial input and experiences, just like a human child it can progressively advance its abilities based on processes such as deep learning.

For example, to test whether the work generated by AI and humans has become indistinguishable, a leading tech company came up with an interesting experiment. They asked the readers to tell the difference between two pieces of work – one generated by AI and the other written by a human. The result of the experiment was not surprising either, it was difficult for a normal person to identify which is which. You can see the experiment here.

The concept of strong AI is more of a theoretical question at this point in time, while some scholars, like Marvin Minsky, are very optimistic about the prospects of AI in a few decades, in 1970 Minsky was quoted in Life magazine, “In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being”. Others absolutely disregard strong AI as a pragmatic concept.

Turing test is often used to test a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior which is indistinguishable from human intelligence. You can read more about the Turing test here. The whole idea behind comparing the nature of the work of the two entities is to determine whether AI is able to create a work worthy of copyright protection. If an AI works in a way that it does not go beyond the inputs determined by the programmer, it serves no less than an instrument or a tool. It was argued by Gerald Spindler that AI may improve ways to achieve a goal but it cannot change it. However, suppose an AI manages to surpass the initial inputs and creates something that the programmer could not have contemplated, does this show an element of creativity? The answer to this question may depend on the result produced.

Take this example, suppose, an artist decides to program an AI software based on her paintings and then subsequently the AI generates a new painting, an important question arises here to what extent the artist influenced the outcome generated by AI? Again, Gerald Spingler gives a detailed answer to this question, he maintains that if the artist used only a certain painting to train the software, then we can say that there is a strong influence of the artist on the new painting because the inspiration or the sources for AI to learn is limited to the specific works of that particular artist. In this case, the work should be attributed to the artist as AI is only serving as an instrument or a tool to improve the outcome. This is consistent with the observation we made earlier that if an AI is not able to think beyond the inputs of the programmer it is no less than a tool just like a canvas or a paintbrush for an artist. Further, if the artist used all her paintings and also those of other artists (contrast it with the limited input in the first case) then the influence of the artist is not meaningful or at best negligible.

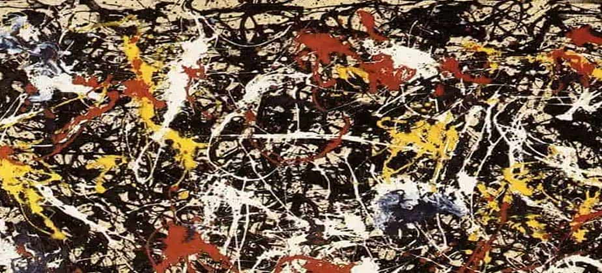

The extent of creativity in an AI-generated work carries with itself intricate problems. Another issue is the copyright claims of AI-generated works akin to modern artworks which are not a product of a deliberative process or inspiration. Consider this image,

Source – Bing Images.

These expressionist artworks, such as the works of Jackson Pollock or Adolf Gottlieb, are a product of randomization. If an AI is capable of producing similar expressionist artworks, these works should be recognized as worthy of copyright protection.

In order to answer whether AI should be treated at par with human beings for copyright protection, the nature of work generated by AI and its similarity with human creativity must be unambiguous. It is not easy to answer what is meant by human intelligence, and any attempt to define AI carries its own intricacies. Scholars across the globe have tried to explain the legal personhood of AI with the help of the concept of consciousness. Searle argues that self-consciousness is a sine qua non for strong AI to exist. Buttazzo, while discussing artificial consciousness, pointed out that – at a neural level, the same electrochemical reactions present in machinery (AI) operate in the human brain. On the other hand, Jasper Doomen reserves his judgment on the question whether strong AI possesses consciousness. But an in-depth analysis of the concept of consciousness is not germane to our purpose, pointing towards similarities between the works of human beings and artificial entities will suffice. In the next section, we will deal with the personhood of AI to address the copyright claims.

Legal personhood

Recognizing the legal personhood of AI entities is a “necessary” step to consider them potential copyright owners, but we still have to navigate whether it is a “sufficient” condition. An inquiry into the possibilities of accrediting AI with legal personhood attracts a host of problems. Before addressing some of them, it is necessary to have a stipulative understanding of the concept of legal personhood. If we advert to the philosophical explanation of the concept of personhood, it is imperative to revisit Salmond’s expression “person”, “any being to whom the law regards as capable of rights and duties. Any being that is so capable, is a person …… even though he is not a man”. Salmond’s understanding is more accommodative and marks a shift from the traditional human-centric approach, at the same time it is consistent with the Lockean idea of legal personality. Therefore, it may be concluded that the term “person”, at least philosophically, does not refer just to certain biological and psychological traits of humans which might encompass both natural and artificial persons.

We have witnessed an increased propensity in the judicial forums to deny copyright protection to entities, such as machines or software, for authorship of the work generated by them autonomously without any human input. This position is substantiated by international jurisprudence regarding copyright claims of non-human entities – Recently, the Review Board of the United States Copyright Office refused copyright registration of a two-dimensional artwork entitled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise.” Although the work was an original work generated by a computer system called the “creativity machine”, the Board rejected the application and found that it could not be registered due to a lack of human agency. The reason behind rejecting the claim was that copyright registration is restricted to “original intellectual conceptions of the author”, and an artificial entity doesn’t satisfy this condition and cannot be regarded as an author.

The Indian Copyright Act was amended in 1994 to accommodate the claims of computer-generated works, section 2(d)(vi) defines “author”, inter alia, “in relation to any literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work that is computer-generated, the person who causes the work to be created”. The prospects of AI-generated works getting copyright protection are uncertain, as the interpretation of the word “person” is contingent upon the traditional human-centric approach. This approach is evident in the judgment of the Delhi High Court in the case of Rupendra Kashyap v. Jiwan Publishing House Pvt. Ltd., where the court rejected the copyright claims of an artificial person, thus reinforcing the principle that only natural persons can claim authorship under the Indian copyright regime. Similarly, In China, a district court, in the case of Shenzen Tencent v. Shanghai Yinxun, emphasized the requirement of human contributions in copyrightable works. Therefore, it can be concluded that the word “person” is traditionally interpreted by the judicial forums across jurisdictions to exclude non-human entities, restricting copyright protection to natural persons.

Restricting legal personhood to human beings is a problematic idea, it is argued that the traditional lexicon meaning of the concept “person” includes the “personhood of living persons only”, but this is a restrictive interpretation of the concept. The legal meaning of a person is contingent upon the ability of the entity to respect legal rights and obligations. Against the backdrop of technological evolution driven by AI, Such a restrictive interpretation of the term person will not be consistent with the complex nature of an evolving society. Today, the concept of a person not only includes a natural person but the law recognizes the legal rights of corporations, idols, rivers, ships, and animals, to name a few non-human entities.

As discussed earlier, the idea of legal personhood of AI comes with a host of implications. One such issue is the accountability of the AI entity. The primary logic behind accrediting legal personhood to AI is to protect humans from any foreseeable or unforeseeable liabilities, which would, in turn, encourage people to creatively engage in commercial activities with the help of AI. If we were to consider this logic, accrediting legal personhood to AI would enable society to accept and promote its usage in human functioning.

Conclusion

In the last couple of decades, AI has developed to a position of individuality from its programmers. It can foreseeably engage in activities that would warrant responsibility and accountability. Therefore, taking into account the state of AI development today and the legal issues associated with the establishment of a relationship between AI’s behavior and human actions, accrediting AI with legal recognition becomes a necessity.

For example, consider a strong AI music album that creates content based on inputs and pre-existing data by employing machine learning algorithms and Natural Language Processing (NLP) approaches. Without the need for human input, it is capable of producing music, films, and other creative works, demonstrating a degree of functional autonomy comparable to human creativity. Now can we grant copyright protection to the AI entity that produced this music album? The current legal framework is silent on this issue. Given the implications of AI’s integration into people’s daily lives, artificial entities ought to be treated as legal persons if they achieve a very high level of autonomy comparable to that of humans.